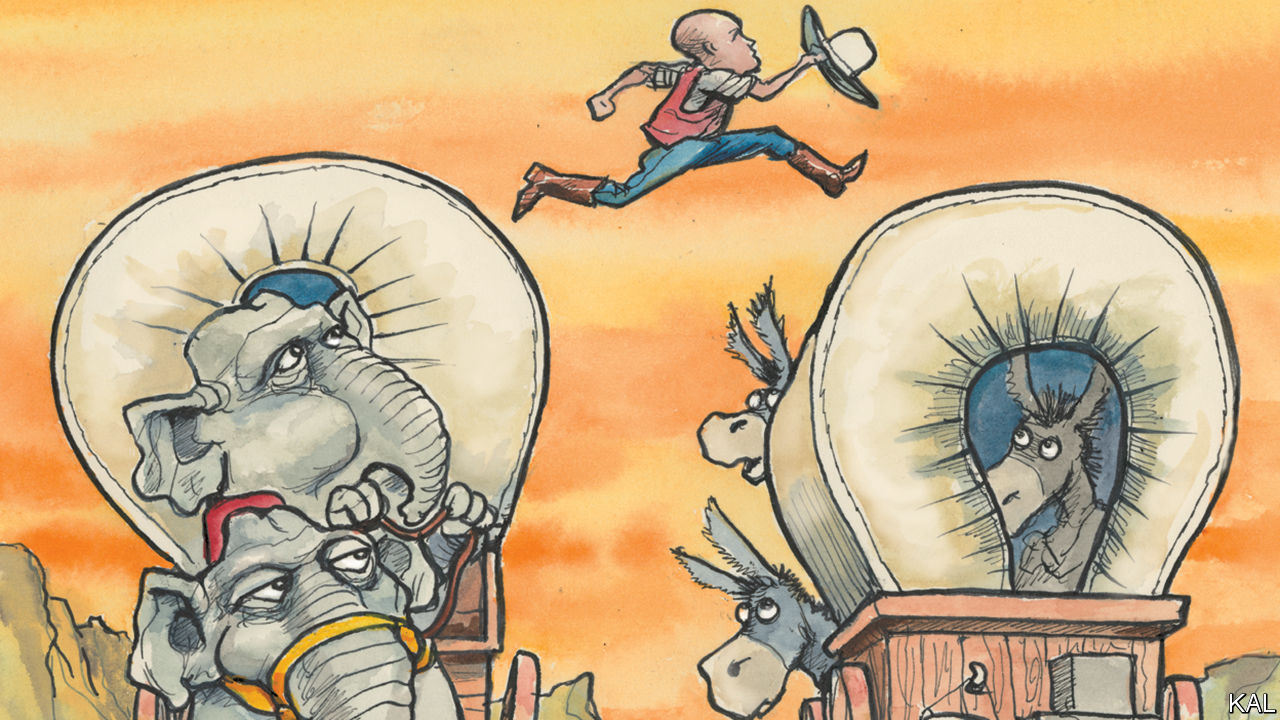

As partisanship deepens, those who change their minds become more precious

AMERICANS ARE “restless in the midst of abundance,” Alexis de Tocqueville observed, continually changing their track “for fear of missing the shortest cut to happiness.” This sense that something better might be around the next corner is visible in choices over where to live: despite a recent decline, Americans are still much more likely than the French to migrate within their own country. It also shows up in the realm of the sacred. Episcopalians become evangelicals, Catholics leave their childhood faith and sometimes come back, Muslims become atheists.

One part of life where this restlessness does not apply is politics. Almost everyone who voted for Donald Trump in 2016 had voted for Mitt Romney four years earlier, just as almost everyone who voted for Hillary Clinton had previously voted for Barack Obama. People who vote tend to settle on a party with which they identify in young adulthood, then stick with it. By contrast, half of American adults have switched religious denomination at some point, according to the Pew Research Centre. The datasets do not line up in a way that makes the conjecture possible to prove, but it is a fair bet that, at least among those most engaged in politics, Americans are more likely to change their religion than to change their party.

Partisanship eats away at the sense that it is possible to think for yourself. Partisanship also obviates the need to take opposing views seriously. Faced with a political decision, such as whether to support Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination, or talks between America’s government and North Korea’s, it is far easier to listen to the people you normally agree with and adopt their view. Weighing up evidence is hard, time-consuming work: in this respect, partisan thinking is another shortcut to happiness.

When thinking is so entrenched, those who change their minds have a kind of superpower, for only they can demonstrate independent reasoning. That explains the fascination with the small subgroup of voters who chose Obama in 2012 and then Trump in 2016. Psephologists and journalists treat these creatures as ancient Romans treated birds, studying their flight paths to see what the omens are. Writers who have switched sides, though less numerous, exert a similar fascination.

The most penetrating criticism of Donald Trump’s presidency has come from people like Bill Kristol, David Frum, Jennifer Rubin, Eliot Cohen, Bret Stephens and Max Boot, whose work is powerful because their conservative credentials are sound. Some of them have remained Republicans, hoping eventually to reform the party from within. Mr Boot has moved further, arguing in a new book “The Corrosion of Conservatism” that the Republican Party is beyond repair and should be “burned to the ground”.

Voiced by a lifelong Democrat, that suggestion would invite eye-rolling. Mr Boot, who devoured copies of William F. Buckley’s National Review as a teenager in California in the 1980s, idolised Ronald Reagan and became the editor of the Wall Street Journal’s opinion pages at the age of 28, cannot be dismissed so quickly.

The American conservative tradition he grew up in rejected the blood-and-soil conservatism more common in Europe. European conservatism developed in opposition to the French revolution; American conservatism idolises the revolutionaries who declared independence. The American style was open, tolerant, optimistic—the opposite, in fact, of the simple certainty offered by aristocratic Europeans in their draughty drawing rooms that things used to be better. Mr Trump offers something closer to that nostalgic tradition, only with air conditioning.

Mr Boot would like to say, as Reagan did of the Democrats, that he didn’t leave the party, the party left him. But Mr Trump’s rise has changed Mr Boot’s perception of the movement he spent 20 years trumpeting. Though aware that some Republicans preferred creationism to geology, or were convinced that the only way to guarantee freedom was to own more guns, Mr Boot took them to be a paranoid few. Now he is the fringe. Having spent decades defending his fellow Republicans from accusations of racism, Mr Boot believes that, though “not all Trump supporters are racist [...] virtually all racists, it seems, are Trump supporters. And all Trump supporters implicitly condone his blatant prejudice.”

From East Hampton to Hampton Inn

The reward for this independence of mind has been a kind of social death. Invitations to weekend at grand houses in the Hamptons have dried up. “This is how all social, ideological or religious movements police their members—by making clear that agreement will be rewarded with greater social standing and support, and disagreement punished with ostracism.”

Some of Mr Trump’s supporters have noted with glee how ineffective the attempts by conservative intellectuals to wrest the Republican Party away from Mr Trump’s control have been. They should be cautious about declaring victory too early. The original neoconservatives left the Democrats, joined the Republicans and ended up running the country for a while, further proof of the outsized influence of those who cross the aisle.

More surprising has been the reception Mr Boot has received from Democrats ever since he started to agree with them. The “most doctrinaire leftists”, he writes, seem to think that nothing short of “ritual suicide will atone for my ‘war crimes’, which upon closer examination seem to consist of supporting an invasion of Iraq that was backed by bipartisan majorities in both houses.” The handful of Trump voters who express public regret are too often treated with the same scorn by the president’s opponents.

Wavering Trump voters, like never-Trump conservatives, pose an obvious challenge to Republicans. But they are putting a test to Democrats, too. Religions know that converts are special, that there is more rejoicing in heaven over one sinner who repents than over 99 righteous people who do not need to. Political parties interested in winning majorities should treasure switchers too.